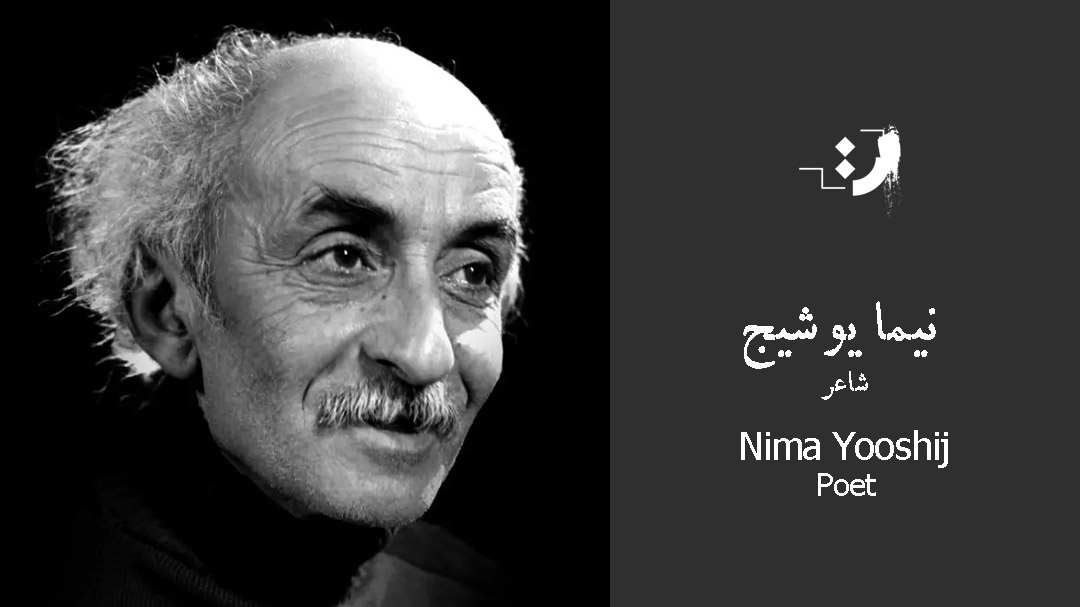

Nima Yooshij

Biography

Nimā Yushij (Persian: نیما یوشیج; 12 November 1895 – 6 January 1960),[1][2] also called Nimā (نیما), born Ali Esfandiāri (علی اسفندیاری), was an Iranian poet. He is famous for his style of poetry which he popularized, called she’r-e now (شعر نو, lit. “new poetry”), also known as She’r-e Nimaa’i (شعر نیمایی, lit “Nima poetry”) in his honour after his death. He is considered as the father of modern Persian poetry.

He died of pneumonia in Shemiran, in the northern part of Tehran and was buried in his native village of Yush, Nur County, Mazandaran, as he had willed.

He was the eldest son of Ibrahim Nuri of Yush (a village in Baladeh, Nur County, Mazandaran province of Iran). He was a Tabarian, but also had Georgian roots on his maternal side.[4] He grew up in Yush, mostly helping his father with the farm and taking care of the cattle. As a boy, he visited many local summer and winter camps and mingled with shepherds and itinerant workers. Images of life around the campfire, especially those emerging from the shepherds’ simple and entertaining stories about village and tribal conflicts, impressed him greatly. These images, etched in the young poet’s memory waited until his power of diction developed sufficiently to release them.

Nima’s early education took place in a maktab. He was a truant student and the mullah (teacher) often had to seek him out in the streets, drag him to school, and punish him. At the age of twelve, Nima was taken to Tehran and registered at the St. Louis School. The atmosphere at the Roman Catholic school did not change Nima’s ways, but the instructions of a thoughtful teacher did. Nezam Vafa, a major poet himself, took the budding poet under his wing and nurtured his poetic talent.

Instruction at the Catholic school was in direct contrast to instruction at the maktab. Similarly, living among the urban people was at variance with life among the tribal and rural peoples of the north. In addition, both these lifestyles differed greatly from the description of the lifestyle about which he read in his books or listened to in class. Although it did not change his attachment to tradition, the difference set fire to young Nima’s imagination. In other words, even though Nima continued to write poetry in the tradition of Saadi and Hafez for quite some time his expression was being affected gradually and steadily. Eventually, the impact of the new overpowered the tenacity of tradition and led Nima down a new path. Consequently, Nima began to replace the familiar devices that he felt were impeding the free flow of ideas with innovative, even though less familiar devices that enhanced a free flow of concepts. “Ay Shab” (O Night) and “Afsaneh” (Myth) belong to this transitional period in the poet’s life (1922).

In general, Nima reformed the rhythm and allowed the length of the line to be determined by the depth of the thought being expressed rather than by the conventional Persian meters that had dictated the length of a bayt (verse) since the early days of Persian poetry. Furthermore, he emphasized current issues, especially the nuances of oppression and suffering, at the expense of the beloved’s moon face or the ever-growing conflict between the lovers, the beloved, and the rival. In other words, Nima realized that while some readers were enthused by the charms of the lover and the coquettish ways of the beloved, the majority preferred heroes with whom they could identify. Nima actually wrote quite a few poems in the traditional Persian poetry style and as critiqued by Abdolali Dastgheib, showed his ability well. However, he felt the old ways limit his freedom to express his deep feelings or important issues faced by society. This led him to break free and create a whole new style for modern poetry.[6]

Furthermore, Nima enhanced his images with personifications that were very different from the “frozen” imagery of the moon, the rose garden, and the tavern. His unconventional poetic diction took poetry out of the rituals of the court and placed it squarely among the masses. The natural speech of the masses necessarily added local color and flavor to his compositions. Lastly, and by far Nima’s most dramatic element was the application of symbolism. His use of symbols was different from the masters in that he based the structural integrity of his creations on the steady development of the symbols incorporated. In this sense, Nima’s poetry could be read as a dialogue among two or three symbolic references building up into a cohesive semantic unit. In the past only Hafez had attempted such creations in his Sufic ghazals. The basic device he employed, however, was thematic, rather than symbolic unity. Symbolism, although the avenue for the resolution of the most enigmatic of his ghazals, plays a secondary role in the structural makeup of the composition.455.

The venues in which Nima published his works are noteworthy. In the early years when the presses were controlled by the powers that be, Nima’s poetry, deemed below the established norm, was not allowed publication. For this reason, many of Nima’s early poems did not reach the public until the late 1930s. After the fall of Reza Shah, Nima became a member of the editorial board of the “Music” magazine. Working with Sadeq Hedayat, he published many of his poems in that magazine. Only on two occasions he published his works at his own expense: “The Pale Story” and “The Soldier’s Family.”[5]

The closing of “Music” coincided with the formation of the Tudeh Party and the appearance of a number of leftist publications. Radical in nature, Nima was attracted to the new papers and published many of his groundbreaking compositions in them.

Ahmad Zia Hashtroudy and Abul Ghasem Janati Atayi are among the first scholars to have worked on Nima’s life and works. The former included Nima’s works in an anthology entitled “Contemporary Writers and Poets” (1923). The selections presented were: “Afsaneh,” (Myth) “Ay Shab” (O Night), “Mahbass” (Prison), and four short stories.

- Birthday: November 11, 1895

- Death: January 1960

- Birthplace: Yush, Mazandaran, Iran

Poet